In 2009, the Explore Apolobamba 2009 expedition took place, which was successful in conquering four virgin peaks and the summit of FAE 3 in the Bolivian Andes. Two years later, the Explore Apolobamba 2011 expedition set off with no less ambitious plans. Here is the second part of the account of what they managed to achieve this time.

Usually, as a goal of my subsequent travels, I try to choose places where I haven’t been before. However, I made an exception for Apolobamba.

When one returns to places they have visited before, they expect to find memories waiting for them. But, more often than not, they find disappointment because the place may not be as magnificent as it once was, the people they met last time are no longer there, and things have changed.

So far, I’ve been lucky with my returns. Will I be disappointed this time? Is señor Ronaldo Vasques still running his little hotel at the main square of Pelechuco? Will he recognize me? Will we be able to arrange transportation smoothly to our valley, and is it still safe there?

The owner of the transportation company in La Paz mentioned something about bus robberies to Pelechuco, carried out by Peruvians at the last pass before the town. He said they were caught, but maybe he just wanted to make money from selling tickets and didn’t want to discourage us from going? Either way, for some reason, there’s now only one company traveling to Pelechuco.

Back to Pelechuco

Hundreds of thoughts run through my head as we just passed through the Ulla Ulla plain, famous for having the largest vicuña reserve, and we’re now starting to climb towards the Pelechuco pass. By “we,” I mean me, Filip, Tomek, and Magda. Blood pressure rises, atmospheric pressure drops. We pass by the white Christ monument and descend towards the lit-up town.

In Pelechuco, as usual, it’s a fiesta! (We recommend the photo report “Non-stop fiesta. That’s how Bolivia parties.”) I feel a bit disheartened. Looking for a four-wheel-drive car among completely drunk, temperamental miners can only bring us trouble. On the other hand, should we just give up without a fight?

We leave our bags with Ronaldo at the hotel and start our search. The atmosphere is intense, but there are also people eager to earn some money. The woman who tried to extort money from us for extra luggage on the bus is trying her luck again. She wants 2000 BOB (around 900 PLN) to take us to Puina. Too much! After an hour, luck smiles at us. Señor Juan Mendoza, not particularly sober but not too drunk either, agrees to take us for 1100 BOB.

The next morning, we stock up on supplies. In the frenzy of shopping, we also decide to buy eggs. We have no idea how to carry them down the valley without breaking them, but we can already imagine the taste of scrambled eggs for breakfast the day after a successful summit attack! We set off.

Juan seems to know what he’s doing. There are no signs of the previous day’s partying on him. He drives carefully but efficiently. We have 50 km to cover, three passes to cross, and two rivers to overcome.

From the beginning, we quickly gain altitude. The road zigzags up towards the Sanchez pass, providing us with breathtaking views and intense emotions. If we are scared, imagine what the boy we brought along must be feeling right now, sitting on the roof.

I try to recognize the places where we slept when we walked with the mule caravan two years ago. During that time, nothing has changed, maybe except for a bit more snow in the upper parts. I know this place won’t disappoint me. I can’t wait to show my companions the waterfall in our valley and the spot I’ve chosen for our base camp! The most enjoyable thing about traveling is sharing experiences with others. I know the rest of the team will be delighted with the valley, and I can’t wait to get there.

The Battle for Llamas

In the early afternoon, we finally reach the point where we can enter the Huancasayani valley. I secretly hope that we’ll be able to set off the same day, but it seems like we won’t be that lucky. While Magda and Filip prepare the first half of the dinner, Tomek and I head out to find transportation deeper into the valley.

Our first attempt is at Juan Sulca’s place, whose small farm is at the beginning of Huancasayani. We only find out that his mules are grazing a day’s journey away, but he might be able to bring them or transport our luggage on llamas tomorrow. Despite his offer, we thank him optimistically and head to Puina to find someone willing to go with us today.

As usual, there are not many adults in the village – a teacher, a few women taking care of household duties, and a dozen children. Most adults spend their days in one of the gold mines located around Puina, Cueary, and Pelechuco.

As soon as we enter the village and start asking about llamas, most people become embarrassed and run away. Fortunately, a few braver boys lead us to the house of one of the miners who took the day off and owns a small herd of llamas. The bargaining begins! The Indian is convinced that he can overcharge us and starts with 100 BOB per day for the work of one animal. Fortunately, I know how much this service should cost in Pelechuco, and to balance things out, I offer a lower price. We argued for over half an hour, but we couldn’t negotiate a reasonable price. To top it off, as we were leaving the miner’s house, the children threw mud at us. We’re really angry!

Meanwhile, the sun starts to slowly set on the horizon, and we realize that we won’t be able to organize the caravan on the same day. Disappointed, Tomek and I return to Magda and Filip with the bad news. The fantastic dinner they prepared improves our mood a bit. For now, we can still enjoy fresh vegetables, bread, and cheese. In a few days, it will all be gone, and we’ll have to rely on freeze-dried food, rice, pasta, and powdered sauces. But that’s for next week.

We also manage to arrange with Juan Sulca that we’ll leave together with his herd of llamas for the mountains the next morning. Although his price is non-negotiable, it’s fair. None of us are optimally acclimatized yet. We spent a few days in La Paz at almost 4000 m above sea level, but I know we can handle more, and our fitness will quickly improve.

On the same day, we decide to set up the base camp. The beginning of the route to the base camp involves a steep approach to the suspended valley. We can admire the winding stream flowing from Lake Sorel to Puina and further into the vast jungle of Madidi National Park. There, the stream will grow into a river, and the water will turn muddy, but for now, we can still admire the emerald thread of water winding below us for several kilometers. We reach the base camp just before sunset. As I suspected, it’s a perfect place for a camp.

It’s not visible from the main valley, there’s a flowing stream, it’s relatively flat, so we can set up our tents, and alpacas graze nearby, while chinchillas can be heard in the distance – it’s exactly as it should be.

The base camp is set up. In the morning, when we wake up, señor Juan is already busy with preparations. I didn’t expect llamas to be such good pack animals. Juan loads 20 kilograms on each animal, and the llamas, complaining lightly, briskly move forward.

Each of us also carries a full backpack, so we are not much faster than our caravan. I got the eggs to carry. I secure them on the outside of my backpack with gray tape to keep them in place. We reach the camp around noon. We pay Juan and bid him farewell. Now, our actual adventure with Apolobamba begins.

In Search of Anchors

The goal of the first acclimatization outing is to find the anchors I left in the mountains two years ago.

We reach the old expedition base in the afternoon. I can’t take my eyes off the sight of the Trata Tata peak, which left a deep impression on me during my previous visit to the valley. Now I have the opportunity to admire it again!

After a short rest on the soft grass, a sip of tea from the thermos, and a piece of delicious Polish chocolate, we start our search. We check stone after stone. We manage to find the spot where we burned the trash, the stone under which Rimi hid the mule harnesses, but there is no sign of the anchors. We are about to accept failure and plan to return to the camp when we finally spot them – they are well hidden under a large, cracked boulder. We were already fed up with anchors, and these were not essential for further activities in the mountains, but these small successes boost morale. We are thrilled like children and return to the base camp full of optimism.

During dinner, an older man with two dogs pays us an unexpected visit. With a gesture of his hand, we invite him to have some cheese sandwiches and tea. Communication is not straightforward – the shepherd doesn’t speak Spanish well, and our Aymara is not the best either, but when people want to communicate, they always find a way. It turns out that the man lives in a stone hut, just a few minutes away from our camp, and he takes care of grazing llamas and alpacas.

After a short chat, he leaves, and we begin to prepare for our first summit attempt, which is scheduled for tomorrow. We have chosen a beautiful pyramid-shaped peak, specifically its mighty southern ridge. We wake up well before dawn and after consuming the somewhat laboriously prepared porridge, we set off.

Initially, the path runs along the edge of the lake, with no significant elevation gain. Later, however, we have to part ways with the lake and start climbing towards the glacier beneath our pyramid. The first signs of fatigue appear. I am troubled by stomach issues, which don’t make things easier. We bypass the second lake, pass by a llama skin spread out in the sun for drying, indicating that people do come here, and head towards the chosen ridge. We tie ourselves with ropes on the rocks and begin the actual climb.

I climb with Magda, while Tomek goes with Filip. To save some time, we use the technique called “pitch climbing.” I set the anchors, and Tomek attaches himself to them and adds his own periodically. The route is not too difficult. We ascend a huge gully on the western side of the ridge. Technically, we could climb here without securing ourselves, but I am frightened by how brittle the rock is, so just in case, I insist that we remain tied together.

The protection is very difficult. It is rare to find a stable crack to place a piton, and the exposed rock blocks are usually loose, so it is seldom possible to set up slings. Hammering in pitons causes the rock to loosen even more. I don’t think I have ever climbed on such poor-quality rock. By early afternoon, we manage to reach the pass. At this point, only one or two pitches separate us from the first summit during this expedition.

However, the climbing becomes more challenging. Here, makeshift protection is not enough. There are fourth-grade difficulties, which might not seem like much, but in such brittle rock, it could be enough to get hurt. When grabbing a hold or standing on a foothold, we cannot be sure it won’t break off. That’s why we place a lot of protection points. We are aware that not all of them are solid, but it’s better than nothing. Finally, we reach the summit.

On the Summit

The joy is slightly subdued by the prospect of a challenging descent route, and the wind is picking up, making it late. So we take only a few photos and start preparing to descend.

There isn’t much space for a proper rappelling anchor on the summit. Therefore, we decide that Tomek will start descending the same way we climbed, and I will go last and collect the gear. We only marked a few places as possible rappel anchors on the way up, so we hope they will work on the way down too. After an hour, we are already at the pass, but the sun is rapidly lowering.

We already know that we won’t make it to the camp before dark, but we want to descend into the valley while we can still see ahead of us. We move with dynamic protection – Tomek leads, and I am at the end. As we descend into the valley, it’s already dark. Two more hours, and we should be at the base. We reach the camp just before midnight, utterly exhausted, but the next day, a sweet laziness awaits us as a reward!

But after the leisure, hard work! Our choice falls on a peak that we tentatively named “Kocimi Uszami” (Cat’s Ears) during our previous expedition to the Bolivian Andes. The upper parts of the mountain have a system of huge flakes, so we hope to find a route between them leading to the summit.

The beginning of the route leads around the same lakes we bypassed the first time. Later, we start ascending steep scree towards the pass. We have to be extremely careful because everything is loose. Every few steps, we stop to catch our breath. Only Filip, indefatigable, runs around and films.

We reach the pass around noon. Now we have to go around the summit from the south and attempt to climb into the system of large rock slabs that we expect will lead us to the summit. The psychological aspect starts making the climb very challenging. Every now and then, we hear stones falling down. These sounds remind us of how fragile and dangerous these mountains are.

After one not-so-difficult pitch, we reach the top of the southern pillar of the mountain. From here, we only need to climb a few dozen meters up a snowy chimney, and we should be in safer terrain. It’s easy to plan, but harder to execute. We set up an anchor and start climbing.

The beginning goes nervously but not too bad. I manage to place a good piece of protection. At the second one, my hands are trembling, and two pitons clatter loudly into the abyss. I hammer in a solid piton, which boosts my confidence. Then, the snow starts. However, it’s frozen, and I manage to create decent footholds, so I continue upwards. Later, the snow structure changes, and I no longer feel a secure base under my feet.

I am about one and a half meters away from the right edge of the chimney, where I see a system of small ledges, which should allow me to climb up without any problems. However, I realize that I haven’t placed any protection for the last 15 meters. I am climbing solo. Fear blocks my attempts to exit the chimney, and my feet slide on the snow. I don’t want to show any panic to avoid scaring Magda, who is belaying me. Finally, I manage to wedge my knee between the left wall of the chimney and the frozen snow.

I feel a bit safer. I take off my backpack and reach for the attached ice axe. I already know that this is the end of climbing for today, and I need to figure out a way to get out of this situation. I start descending on the pick of the ice axe. After a few minutes, I reach the piton I placed earlier. I check it again for reassurance and ask Magda to lower me. I need a few good minutes to regain composure. I ask everyone if anyone wants to lead this pitch, but no one volunteers.

This time, defeated, we start descending. From the pass, we walk on the snow, so we reach the base of the mountain in half an hour. Now it’s safe…

The third goal of our trip was to climb the highest peak of Trata Tata. In 2009, we managed to climb two of the four peaks of this massif, but the highest remained unclimbed. This time the road goes south. We pass a shepherd’s hut with whom Filip made friends during the previous trip and whom he visited on every non-climbing day. Then we cross the river flowing at the bottom of the Huancasayani valley. This is where the arduous, several-hundred-meter-long approach to the pass begins.

Fighting Weakness

Without looking back at each other, we slowly but steadily ascend. Everyone is battling their own weaknesses. We reach the pass at exactly noon, and Magda informs us that she can’t go any further. In such a situation, I want to order a retreat, but eventually, I give in to Magda’s persuasions to give it one more try. We agree to communicate through our walkie-talkies every full hour. Leaving Magda basking in the sun, we continue onwards.

The ascent is technically easy but very exhausting. Loose small stones mixed with sand quickly drain our energy. However, we remain very determined. The failure on Kocie Uszy and the desire to conquer a five-thousand-meter peak on this expedition push us forward.

Finally, we reach the rocks. The wind picks up, and we can feel the summit getting closer. The terrain is mostly easy, occasionally a bit more challenging, but we decide not to rope up to save time. Firstly, the sky starts to cloud over, and secondly, we worry a bit about Magda since we haven’t been able to establish contact with her. At last, we reach the summit. We know it’s still early, and the way down is easy, so we allow ourselves to simply enjoy the moment.

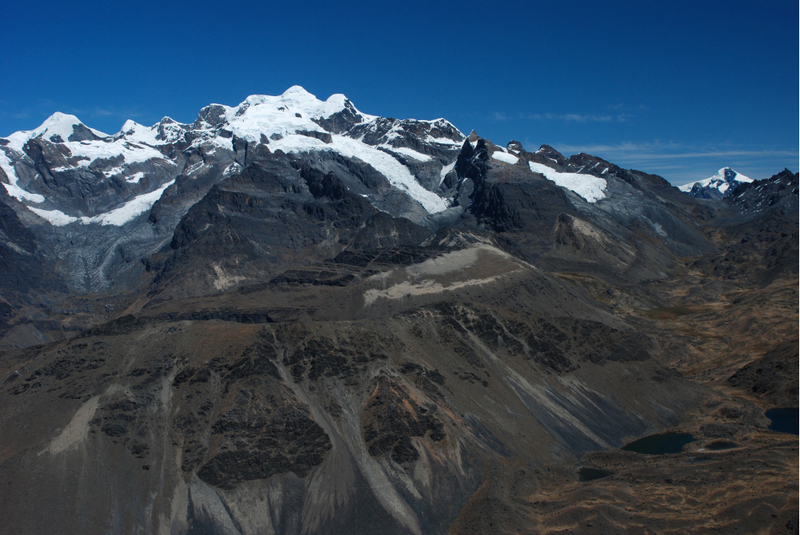

We act like crazy people, goofing around, taking photos, and admiring the surrounding peaks. From here, we can clearly see that there won’t be a shortage of demanding, unclimbed peaks in the valley for several more expeditions.

While ascending the scree was quite challenging, the descents in such terrain are pleasant and straightforward. After an hour, we manage to return to the pass where Magda is, and we can begin the march back to the base. Descending along the western slopes of the mountain, we have the opportunity to admire the fantastic patterns formed by the peat bog beneath us. Two years ago, we almost got stuck in it. So now we know that we can marvel at it from afar, but it’s better not to get too close.

First at the Summit

But this is not the end of the expedition. Since we have already conquered two virgin peaks, we set our sights on another peak in the main ridge of Apolobamba, and consequently, the Andes. Surrounded by the most characteristic peak in the Huancasayani Valley – Kura Huari – there are two lower summits. One of them was climbed in 1997 by a German expedition called JEAV and named FAE 7. Eleven years later, participants of an American-New Zealand expedition attempted to climb the second unclimbed peak, which they named Rumi Mukuku. After analyzing reports from both expeditions, we concluded that they actually climbed the same peak. Now, we want to take advantage of the mistake we discovered and be the first to climb the second of the mentioned peaks in the vicinity of Kura Huari.

It’s clear that acclimatization has done its job, as our pace is much better than on our first attempt. We quickly gain altitude and still have the energy to talk. At one point, I spot a fox – about fifty meters away from us. I point it out to Magda and Tomek, who confirm that they see the fox too, traversing quite steep, snowy slopes and calmly disappearing behind the ridge along which we’re moving. Could it be a collective hallucination? But seeing the fox makes me lean towards this option.

Eventually, we reach the glacier. We put on our crampons, tie into the rope, and start to make our way carefully. The summit we’ve chosen looks terrifying. The only potential route leads through a fifty-meter high, steep couloir. No one is willing to take the risk on such fragile rock. Instead, we spot another summit in the northern ridge that looks promising. I’m not sure if it’s FAE 3, which we climbed in 2009 since I’ve never seen it from this perspective before. We head towards the ridge to make sure. It turns out to be FAE 3 indeed.

The route upwards doesn’t seem difficult, but it’s not beautiful either. We decide to descend onto the glacier and approach the mountain we were supposed to conquer. When we begin the ascent, we realize that the ice is covered by a layer of several centimeters of snow. It’s unlikely that there will be an avalanche, but the slope is about 50°, and its structure is layered – it’s not worth taking the risk. Our journey has been fantastic so far with stunning views, so we have no regrets – we descend.

We head east, and in front of us towers the massif of Yagua Yagua. I haven’t heard of it being climbed before, but it’s not a challenging climbing objective either. On the other hand, it’s the last high peak before the vast jungle of Madidi National Park. It’s a natural choice for our final mountain goal.

The first surprise on our way is a very deep valley. I thought we would be walking on relatively flat terrain to the base of the mountain, but right from the start, we lose about 150 meters in altitude. From there on, it’s steep but easy, and we quickly gain elevation.

We reach the col in the southern pillar before noon. Here we must rope up. While the path leads through scree, the constantly sliding rocks and the steepness make it necessary. Filip and I lead, and Magda and Tomek collect the gear. However, since the route is very winding, it takes a lot of effort to communicate and transfer the rope. Everyone is tired, and even Filip, who usually films non-stop, starts to lose his enthusiasm. We reach the upper section of the peak.

We have two potential options – either ascend a fourth-grade terrain a few meters to the ridge and reach the summit, or climb a massive, slightly ascending slab to the east and try to find the way to the top there. Initially, I try to climb to the ridge, but the lack of protection and three successive holds that crumble dampen my enthusiasm. We’ll have to find a better-protected place or an easier route. We traverse the slab. It turns out there’s an easy way to the summit at the end of it. And there it is – a stone wall. Although there haven’t been any documented ascents of this peak, it seems that the locals have also found enough reasons to climb it.

The view is breathtaking. From here, we can see the azure Sorel Lake, several other navy-blue pools, streams winding through the landscape, the white-capped Chaupi Orco – the highest peak of Apolobamba, and the vast Madidi jungle. After a moment, an enormous condor appears a few meters above us and tries to chase us away from the summit. Filip, of course, films it, and I, of course, photograph it.

The descent goes without any major issues, and according to plan, we reach the base camp quite early. The next morning, Filip and Magda go down with part of the gear to intervene in case señor Juan Sulca forgets about us. Tomek and I dismantle the tents, burn the trash, and pack the rest of the equipment. The shepherd arrives with his dogs – Pusita and Oko – to bid us farewell. Juan Sulca also arrives as planned. Both he and Juan Mendoza converse animatedly in Aymara and pack our things on the llamas. Whatever we haven’t used during the mountain action, we share between the two of them. With a slight tinge of regret, we begin our descent. The llamas dash forward, and I stop every now and then to take pictures.

When we reach the road, Juan Mendoza is already waiting. We pick up Juan Sulca and his wife, as well as two young boys from Puina, and head to Pelechuco. Four hours later, we can raise the first toast to a successful expedition.